By Brian Beadie

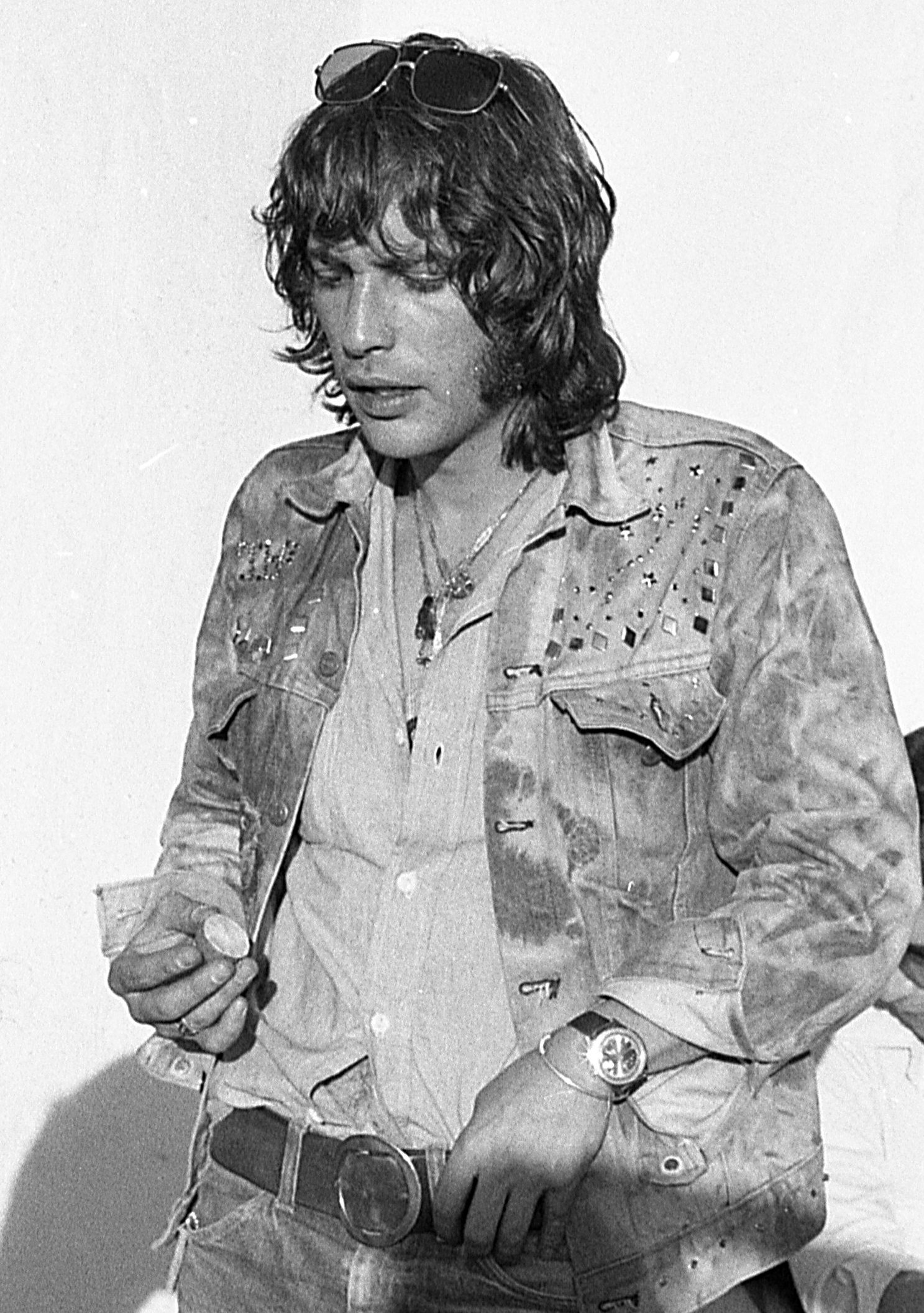

Enter Hernando Toro Botero, the remarkable Colombian artist who is the subject of a new documentary by Adriana Bernal-Mor and Ginna Ortega, and an exhibition presented by Cinemaattic, his first in Scotland. Born in 1948 to a working class family, he would develop an interest as a child in one of the more quotidian, blue collar artforms, photography, but have no aspirations to go to art school, or develop a career in the form. He would move to Bogota in the late ‘60s to take advantage of the Bohemian lifestyle in the city, funding his debauchery with modelling, then a bit of coke dealing. This would prove to be a career he excelled at, pioneering dealing from Colombia to Spain, where he lived something of a rock star lifestyle, until he was caught.

Hernando Toro Botero. 70s

Many artists have, of course, indulged in and been inspired by drugs, and cocaine is the drug of choice for Latin America. Toro, however, may be the only one to have been forced to have become an artist because he was caught dealing them, though the legendary Brazilian founder of Tropicalia, Helio Oiticia, famed for his portraits of Latin American cultural icons drawn in the substance (and the work infamously snorted at the opening) would also be busted for dealing the substance.

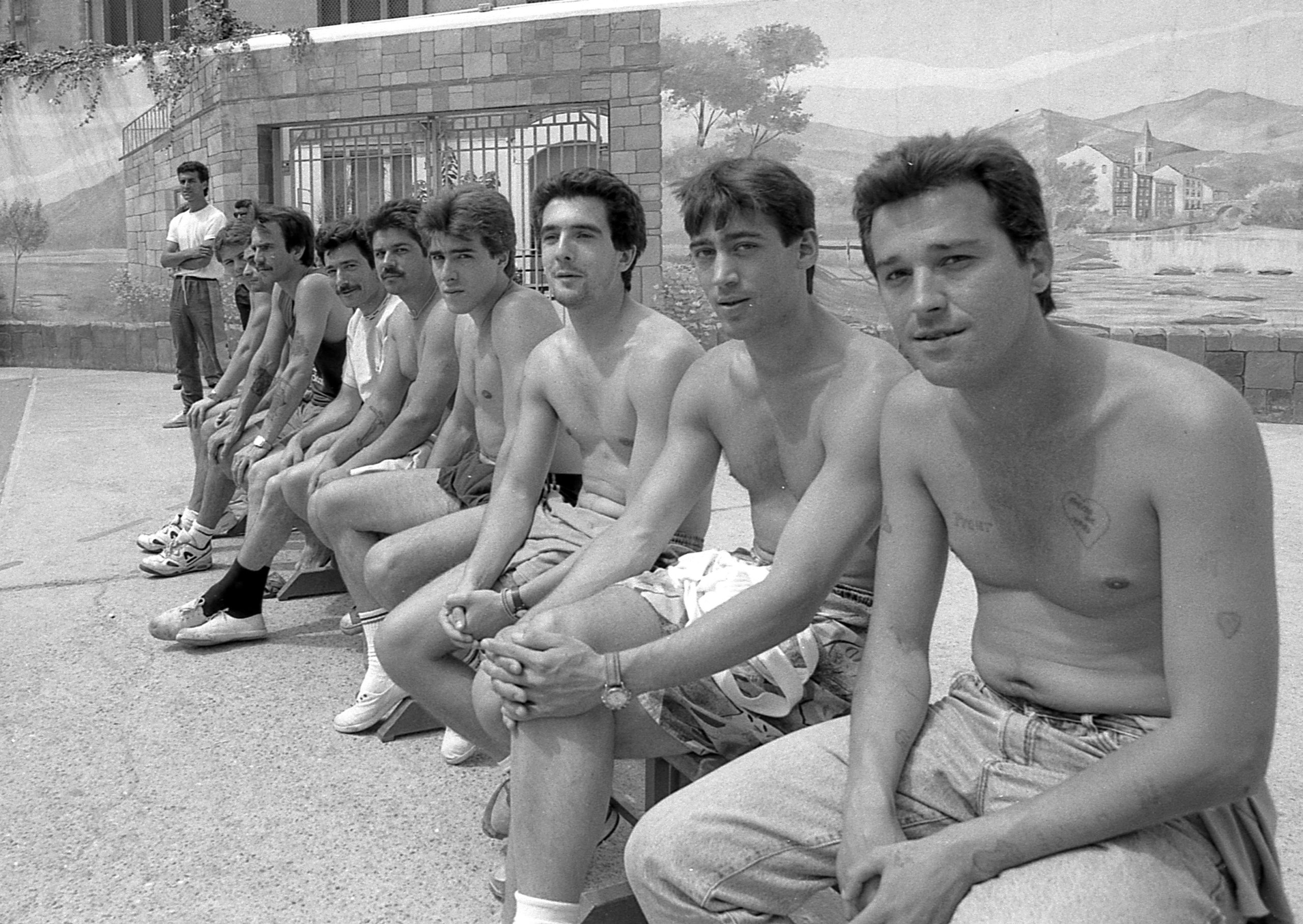

This is because, while serving a lengthy prison sentence, Toro would rediscover his love of photography, partially as a means of keeping himself together, and go on to run photography workshops for his fellow prisoners. He was, in the words of one critic, “condemned to be one of the greatest Colombian photographers of all time”. There is no doubt that the work he produced there is extraordinary, especially given the circumstances. La Modelo prison in Barcelona, where he was incarcerated, was reviled as a symbol of Franco’s repressive government, which would collapse while Toro was there, but he would manage to create a body of images which were both incredibly subversive yet deeply human, treating his subjects on the level, rather than seeking out the abject as subject. One of the most perceptive writers on photography, John Berger, would ask rhetorically, “Does this work help or encourage men to know and claim their social rights?” in 1960. Toro’s work emphatically does, as his subjects become practitioners of the form themselves, and create cards to communicate with their loved ones outside the carceral world. If prisons are supposed to be places of confinement, Toro explores how they simultaneously create alternative spaces for community, and forums for unconventional expressions of being, outside social norms.

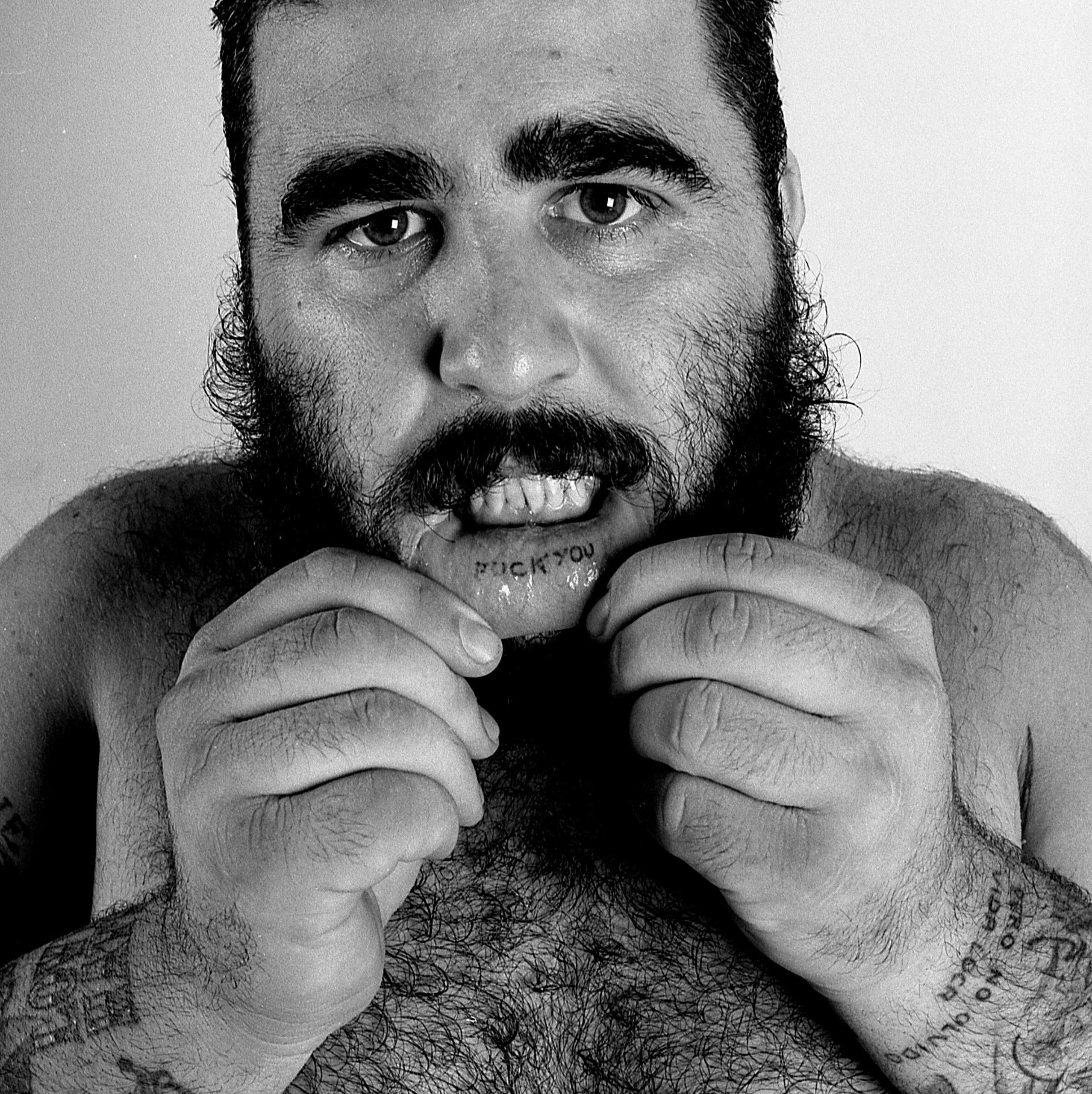

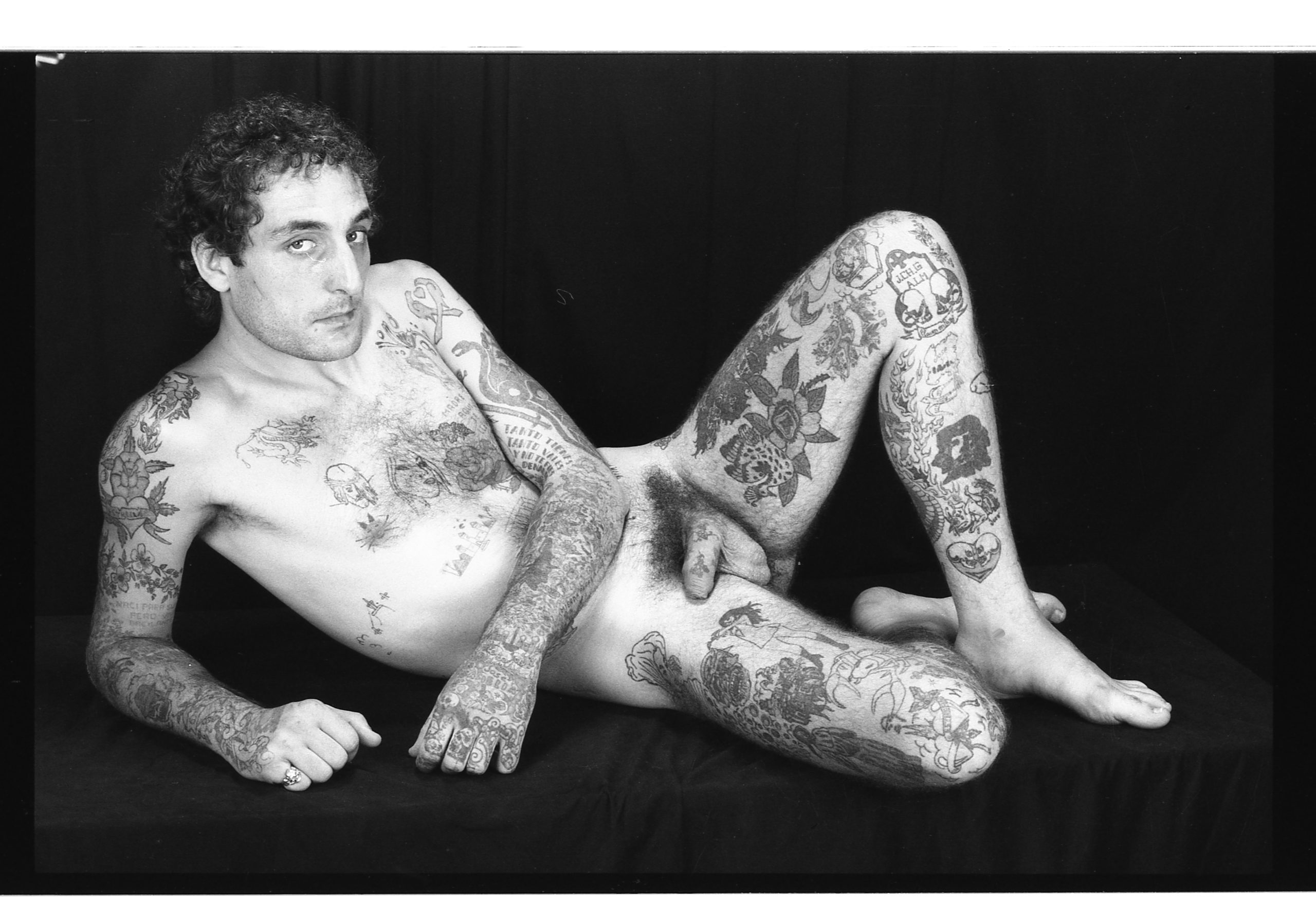

Prison would certainly supply him with an incredible gallery of characters to play with, such as The Sparrow (Gorrión), a strikingly handsome tattooed thief, whose tattoos would give him away in an ID parade, and whose looks would attract unwarranted attention in prison, where he would stab a man to death to fend off a sexual assault. In an incredible series of photos, Toro presents him defiant, staring at the viewer above his arm, emblazoned with the motto ‘Mierda para la justicia’ – shit for justice – then explores his decorated body, before zoning in on his tattooed penis (Lacanians may recall the digression in ‘The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis’ where Lacan discusses the fascination of such an object). This even prompts Toro into a monologue on the – not easy – process of tattooing a penis in the film, one of many fascinating anecdotes he supplies, although he may not be the most reliable narrator. As he states at one point, “Coke heads and drunks talk a load of shit.”

Gorrión / “The Sparrow”

One thing that’s for certain is that his photos garnered attention, leading to exhibitions and even a grant from the Catalan arts establishment, allowing him to develop his career as ‘the prison photographer’, if not to attend his openings. He would be hailed as ‘the master of light and darkness’, a tribute to the acute focus of his portraits, with their subjects singled out in chiaroscuro, and compared to Mapplethorpe and Fellini.

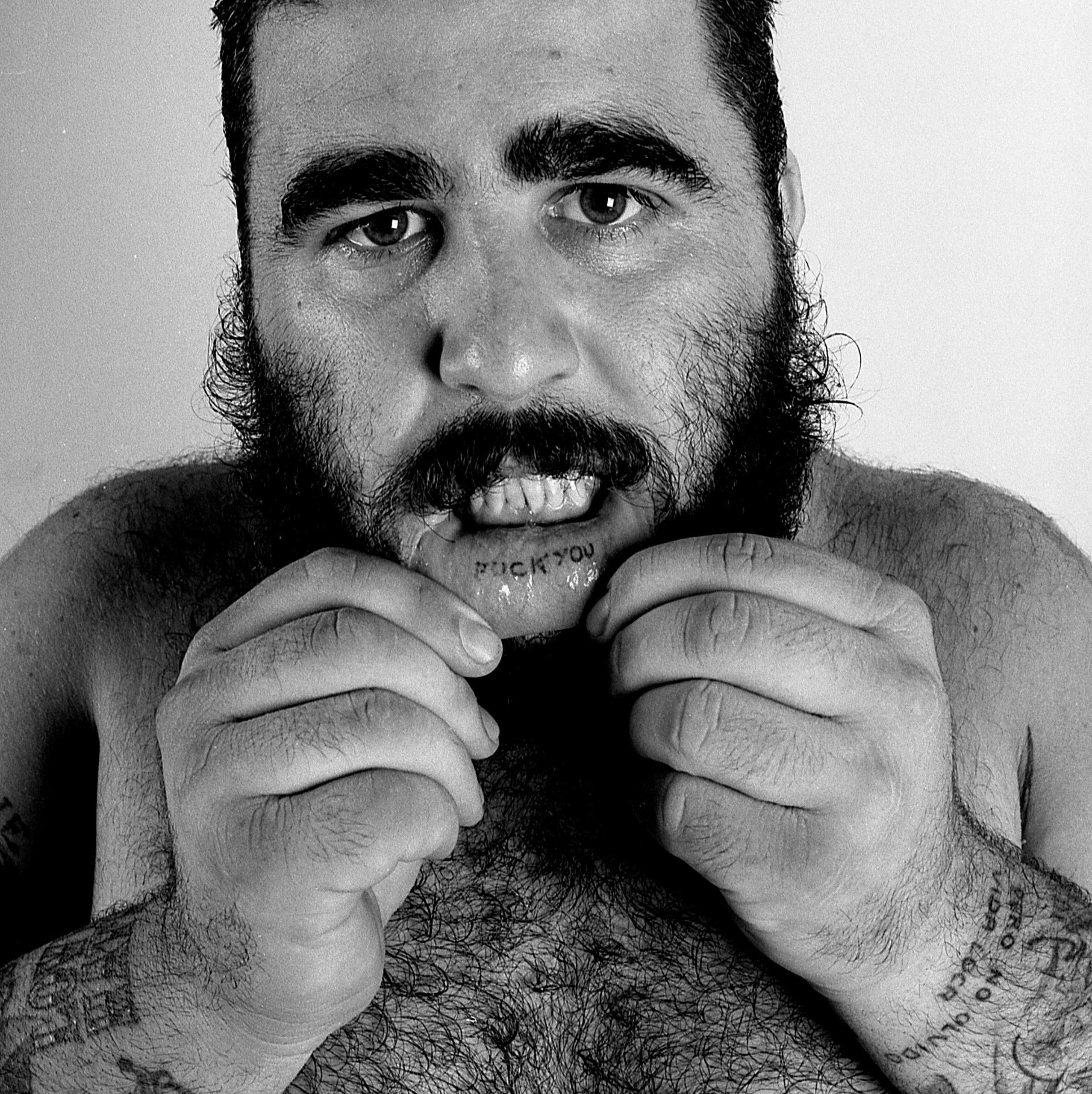

The Mapplethorpe comparison is apt, if partially unwitting on Toro’s part, in that – while he himself may be an avowedly heterosexual artist and a bit of a Latin macho – many of the portraits do have a homoerotic subtext. Many of his subjects were queer, homosexuality itself being illegal under Franco’s regime, not to mention the ways in which ostensibly ‘straight’ men can reconfigure their sexuality in a carceral setting. His work begins to feature trans subjects and drag, some of whom were happily married in the outside world and only realised their true selves in captivity, one other subject – who sounds like they’ve stepped out of a Genet novel – lived a double, schizoid, life as a violent thief and drag queen, until Toro encouraged them to become a model.

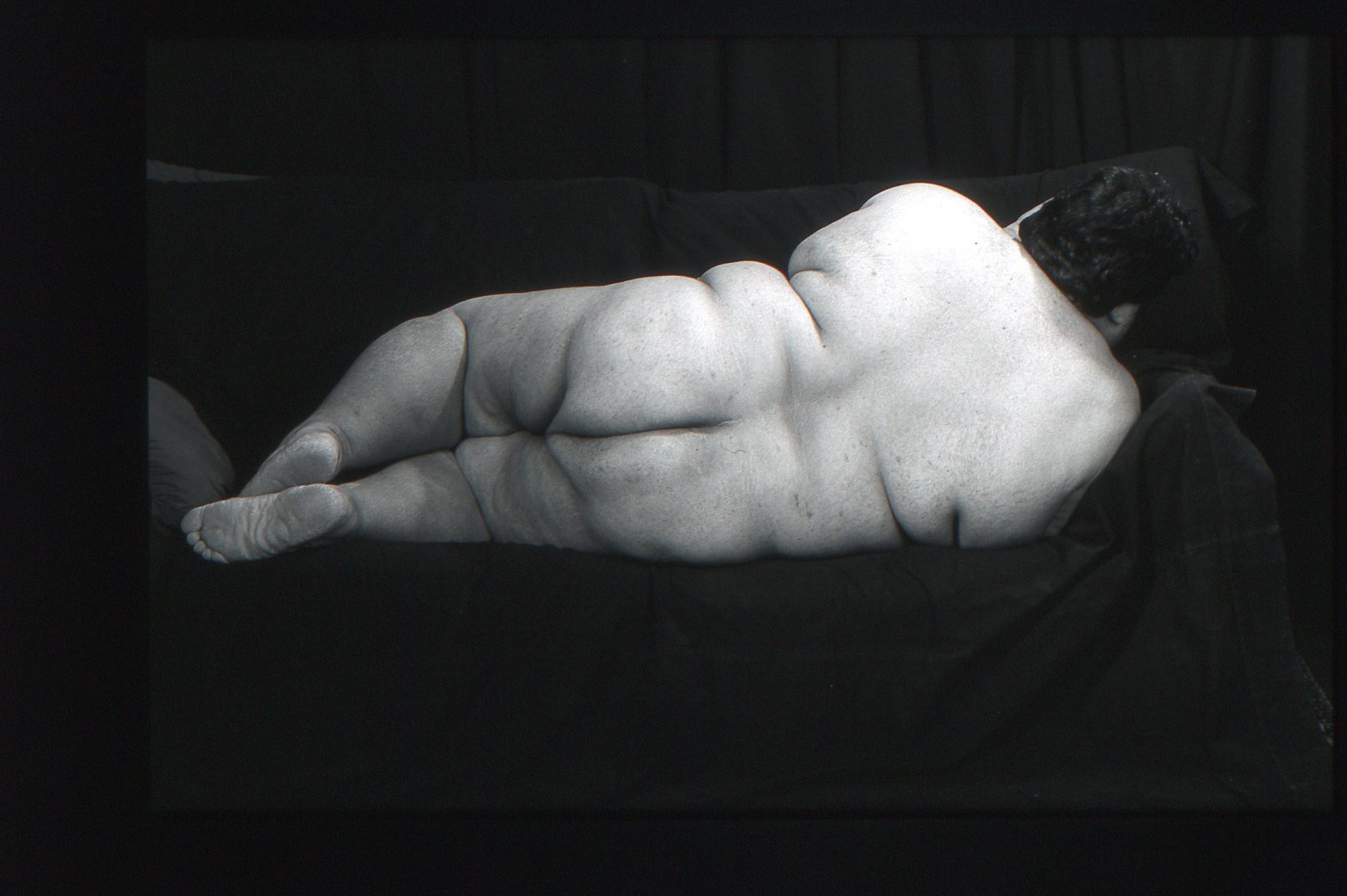

The Fellini comparison may well be apt in Toro’s interest in human extremity, evinced at an early stage by his photos of ‘Fat Fernando’, a morbidly obese prisoner who Toro convinced to pose gleefully naked, his camera enraptured by the infinite ripples of flesh upon flesh.

Gordo Fernando / “Fat Fernando”

Both of these aspects of his work would converge during his post-prison career, when, working for gay magazines, he would focus on the carnivalesque drag scene in Barcelona. This was a city where, post-Fascism, queer people were making up for lost time in a euphoric burst of gender transgression, some of which is more akin to what contemporary practitioners like Christeene would term ‘drag terrorism’, rather than just drag.

Drags / Barcelona

If there is one thing all his models and subjects have in common, it is, as Toro states, that “they are beautiful people, they are not used to being photographed, and they have so much to give.”

These photos are pretty much timeless, but with the contemporary explosion of interest in challenging traditional notions of gender, very much speak to the moment, which has helped bring Toro’s work back into the public eye. He’s now had eighty international exhibitions, won awards, and is currently documenting Colombia’s burgeoning drag scene. As he notes at the documentary’s close, where he’s seen enjoying attention at an opening he’s now finally able to attend, he’s taken on the mantle of a classic, alongside the most feted contemporary Colombian artist, Miguel Ángel Rojas. Intriguingly, Rojas’ work also foregrounds both queerness and the prevalence of cocaine as a subtext to Colombian culture, although he achieved his fame through the more conventional route of art school and respectable prism of conceptual art. They’re both remarkable artists in their own right, and taken together, provide a remarkable guide to the complexity of Colombian society, and richness of its visual culture.

Alex the Motobiker. “Los centuriones de Barcelona.”