The world we inhabit is collapsing around us, whether under flames or floods, the political structures that underpin it are decaying and prone to disruptors as late capitalism no longer works for anyone except a select band of techno feudalists, all watched over by technologies that are surveilling us and stealing our data, in order to imitate and then surpass us. Stop me if you’ve heard it before. How are filmmakers reacting to the present, extreme, metamodern moment? Many seem to be trying to cling onto the tattered remnants of the 20th century, with an endless procession of remakes, reboots and nostalgic, ironic quotations of films that were made fifty years ago, and were much better than their pale, contemporary shadows.

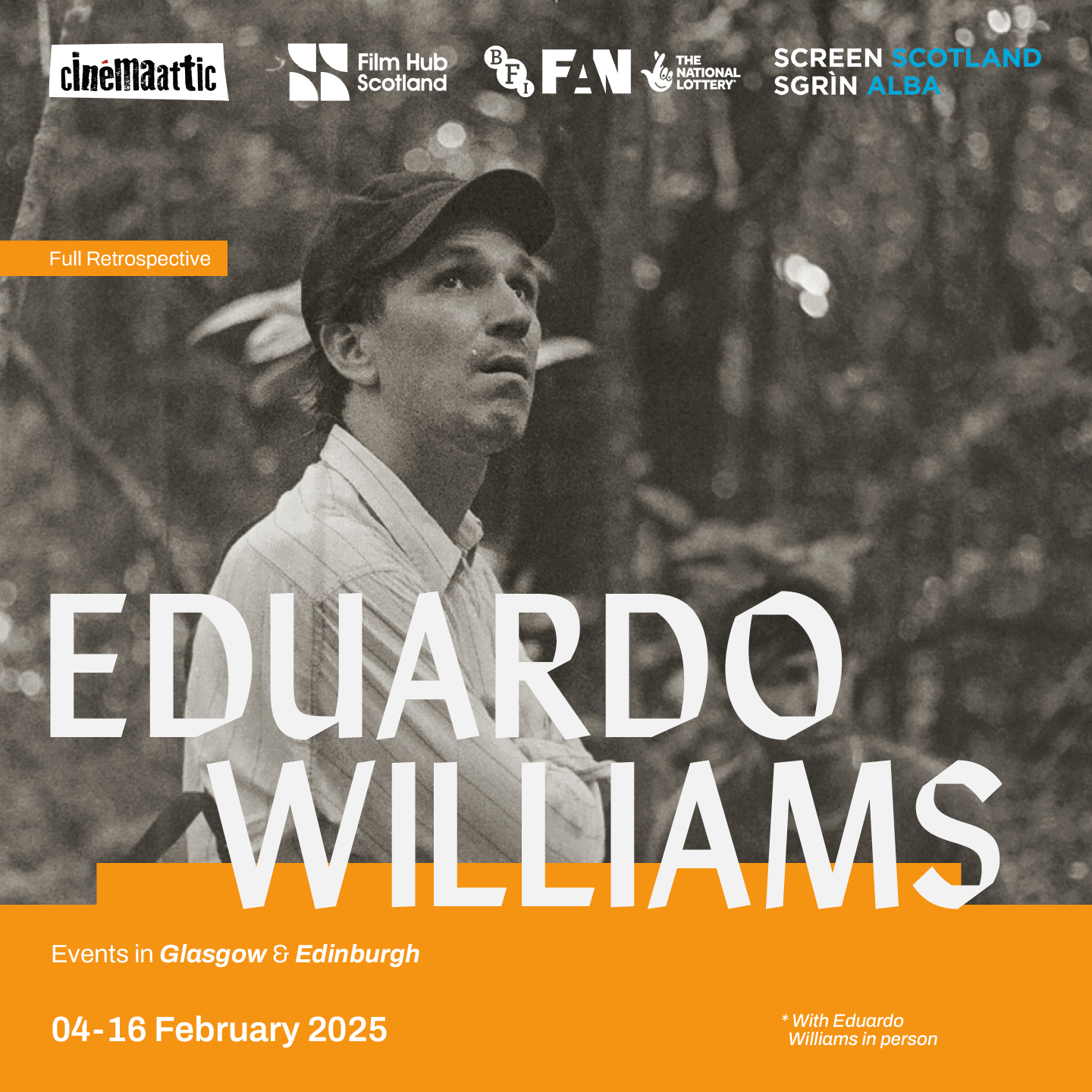

It’s a relief then to come across a filmmaker like Eduardo Williams (‘Teddy’ to his friends), whose films seize on the present moment, and may explore the uncertainties and possibilities open to us better than any other filmmaker currently working. I first became aware of his work when two separate people sent me his first feature The Human Surge, saying ‘you need to see this – it’s the future of cinema’. I didn’t think it was actually the ‘future of cinema’ (whatever that may prove to be), but I did think it nailed the experience of living in 2017 – the year of its making. Having seen its ‘sequel’ last year, The Human Surge 3, I think he may actually have made the most futuristic, least backward-looking film of the decade so far.

Born in Argentina, Williams is a cinematic globetrotter, but one who has never visited Scotland – until now. Cinemaattic are very excited to have lured Williams from Greece where he’s safely sheltering from Millei’s libertarian regime, which is paralysing that country’s incredible film scene as you read this.

Why did his debut provoke such excitement amongst certain critics and audiences, winning it the Golden Leopard at Locarno Film Festival? The Human Surge is that rarity – an experimental film that is actually experimental, and constantly one step ahead of the viewer. It opens in a flood swept Buenos Aires, where a young man has lost his dead end job, and is just trying to survive. The film appears to be pitched somewhere between documentary and fiction, driven by an incessant forward motion, the camera relentlessly tracking its characters until they end up in a room performing desultory sex acts in front of a webcam for money, which then transitions to a webcam in Mozambique, where a group of young men are doing…exactly the same. And the film then follows them.

The themes of human connection and their intersection with technology are beginning to emerge, but while on first viewing (certainly for an older, straight viewer like myself) young men from the Global South doing sex work may seem hopelessly exploitative, there are opportunities for play, and queer sexual expression also being made available to them (as a younger queer friend laughed at me for being prudish).

One of the most extraordinary shots in contemporary cinema then transports us to a tropical paradise in the Philippines, where, in one of the film’s greatest ironies, the characters are desperately looking for an internet connection. Some have found this all quite bleak – as one of my friends said to me, ‘Teddy Williams hates humanity.’

When I put that to Teddy, he just laughed – he really doesn’t. (‘Well, sometimes, I do”, he did add). And The Human Surge is quite a benign, almost Zen-like film – it’s hard not to disagree with the robot’s mantra at the climax, ‘OK…OK’, as chilling as that scene may initially be.

Once you’ve seen The Human Surge, you’ll realise the absurdity of launching a franchise from such a cinematic premise. However, in a sense, Williams had already made ‘The Human Surge 2’, or at least presaged the film, in the beguiling shape of his short Parsi, where he experimented with a GoPro 360 camera tracking the movements of a group of young queer people in Bissau, whether on foot, skating or car, creating a sense of perpetual motion accompanying the text. This is from the poet Mariano Blatt, and his ongoing unfinished – and perhaps unfinishable – poem No es (It Isn’t), a series of increasingly absurdist non sequiturs, with a comic, often sexually provocative (ie very gay) streak running through it.

It’s been said that poetry is unfilmable, and generally it is, though Parsi triumphantly finds a way to do so that isn’t total cringe, and works as a film in its own right.

Williams would expand on this technique with The Human Surge 3, shooting with a 360 degree eight lens camera. This footage was then edited by Williams’ own gaze through a VR headset to fit a cinema screen, where he deliberately pushes the footage to the point of glitching, a disruptive technique which the film embraces and endorses as an aesthetic of its own.

While this film may not be based on poetry, the form itself is genuinely poetic – not in the cliched sense of being ‘lyrical’ (though there is much startling beauty here) but in the way the film moves, abandoning anything resembling a plot to establish a series of visual and thematic rhymes, to pursue a new form of cinematic freedom, motivated more by dream logic or free association.

There are definitely some characters, a Japanese AI researcher, a Cuban data analyst, united both by their precarity and their sexuality, but this film doesn’t do anything as mundane as backstory or character development – they function more like avatars, prowling through vectors, which are distorted by the interaction of Williams’ gaze with the technology. There’s much talk of transnational cinema today, but this film pushes it to new levels, by not only being shot on three continents, but morphing them into some Utopic future Pangea, which the characters have willed into being through their connection, despite the indignities of their day jobs and the exigences of their environments. In a sense, it’s the ultimate hangout movie.

The disorientating final effect can feel like watching a mutant hybrid of a Michael Snow film while playing an RPG, or lucid dreaming. While this may be initially difficult to adjust to, it pays off with visual fireworks and, even, a touch of transcendence for the climax, which has to be seen to be disbelieved – as one character says, “Some explosions happen slowly.”

In the face of so much anxiety around technology, and its impact on politics, the natural world and the inner space of the human psyche around the world, Williams’ films remind us that another world is possible, and has never been so necessary – nor so potentially within our grasp, if we really desire it.

Words by Brian Beadie